The Art of Two Cultures: How My Intercultural Wedding Gave Me a Glimpse Into Marriage

The last time I was in Taiwan was in the "before times"—before the start of the pandemic, before the fear of an invisible virus kept us all six feet apart, before my partner and I had experienced the joys of creating a wedding reception seating chart. It was the fall of 2019, and we were newly married, having exchanged vows in a Seattle courtroom on a rainy Friday night with our parents as our only witnesses. Now we were on a plane bound for Taiwan, my family's country of origin, to celebrate our nuptials with my relatives, many of whom I'd only seen once every few years. My in-laws were fortunately able to carve out time in their busy schedules to make the trip with us, too, and my brother and sister-in-law had reworked their travel plans to be there for our wedding luncheon. It was, in so many ways, a once-in-a-lifetime event.

Growing up, my mother often advised me that it would be best if I found a partner who shared my same cultural background. She and my father had immigrated to the States from Taiwan in 1982, five years after their own wedding banquet at a fancy hotel restaurant. "Best," she said, because it would make the marriage itself so much easier. "Best," she meant, because we wouldn't have to explain ourselves or our customs to each other—ostensibly, my hypothetical partner and I would each come to the union with the same set of expectations for how a marriage should be.

It wasn't a hard and fast rule, but it was an oft-repeated sentiment that wormed its way into my ear and likely subconsciously influenced who I chose to date. I understood, in theory, why she said this, and as a good immigrant daughter, I tried my best to appease my parents: I dated sparingly, and always with my family's concerns in mind.

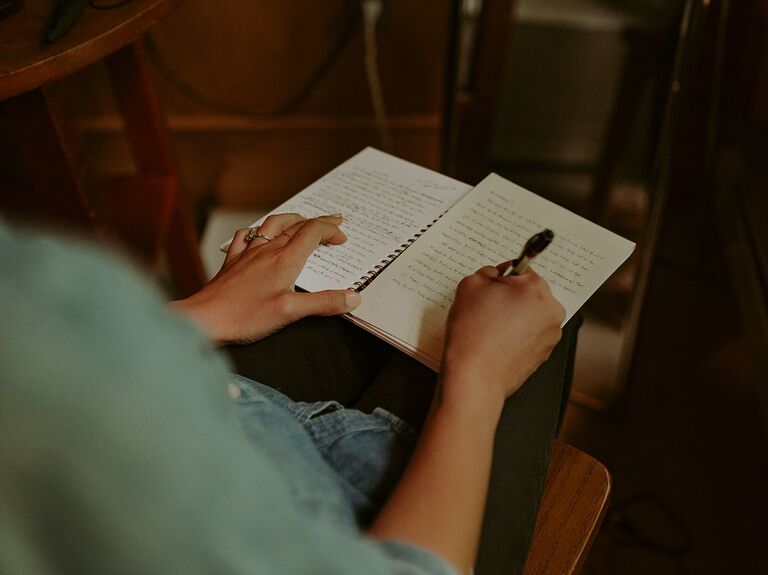

But, as we know, life often has other plans. I met my now-husband when we were two grad students studying creative writing in New York City. Not only that, but we were both nonfiction writers, mining our memories and laying our findings bare for our classmates to inspect and poke and prod. I was drawn to his witty humor, his thoughtfulness, his curiosity about the world. We became fast friends, and a year later, more than friends. We went on what we both deemed "un-dates" for several months, initially downplaying our relationship until our classmates called us out for this pointless ruse and we conceded: yes, we were an item, and yes, we were in love.

I still remember calling my parents to let them know that I was seeing someone and describing him glowingly. My mom interrupted at one point to ask, with the slightest hesitancy, "Is he… American?"

For my parents, "American" was still synonymous with "white," though by that point, they'd lived in the States for more than 30 years. What she was really asking was whether or not my new boyfriend was white, and whether or not I'd considered how this might impact my future, hypothetical marriage. (We'd only been dating for a few months at that point.) I responded with a chipper "yep!" and held my breath, waiting for her reaction.

"You sound so happy," she said.

And that was that. To my surprise, my mom seemed satisfied with my answer and continued the conversation without giving my confirmation much of a second thought. For all of her hand-wringing over the years, it turned out that my mother's main concern was less the ethnicity of my partner and more the brightness in my voice, something she could sense through the phone from 3,000 miles away.

Five years later, in Taiwan, I was suddenly very conscious of not only my partner's whiteness, but also my own Americanness, my foreignness in the motherland. I was born and raised in the States, so to say that I was "returning to" Taiwan is a bit of a misnomer. But I did feel, in light of the circumstances, a certain kind of pride in being able to introduce my husband and my in-laws to the country I'd grown up visiting every other year—its dense humidity, its lush city parks and cracked, uneven sidewalks; its vibrant aliveness and the warmth of its people.

At the wedding luncheon, my partner and I wanted to pay homage to the merging of our two cultures, so we asked our parents to prepare brief speeches to share with my gathered relatives. My sister-in-law translated my in-laws' speeches from English into Mandarin, and my brother translated my parents' speeches from Mandarin into English, a process rendered human by everyone's nervousness and imperfect interpretations. This was a new situation for everyone involved, and though there were starts and stops, our parents' love shone through clearly amid the jumble of languages, even in phrases that resisted translation.

"白头偕老 (báitóuxiélǎo)," my mom said.

"May you grow old together," my brother translated. He didn't mention the bit about white hairs.

Traditionally, in Taiwanese culture, it is said that a woman is "married out" of her family and into her husband's; there are a number of rituals that often take place to signify this new life chapter—the groom's family must offer the bride's family a gift; the groom must then ceremoniously pick the bride up from her home and engage in a series of "door games" to prove his worthiness. Then there's also the tea ceremony, a time for the bride and groom to express their respect and appreciation for their parents' guidance.

We had noticeably done none of these things in their traditional form (hard for my partner to pick me up from my home when we were already living together), but in retrospect, we had actually done them all—just in our own way. I wanted to preserve my Taiwanese heritage even as I was being married "into" a white American family, and our wedding ceremony felt like an important stage on which to showcase this cultural coming together.

My in-laws had prepared little gifts for each of my mom's siblings and my grandparents (specialty chocolates and smoked salmon from Seattle), which took on the symbolism of a Guo Da Li, or meaningful presents from the groom's family to the bride's. My partner had been asked to shave down his ginger beard for the banquet, a testament to his devotion, given that I'd never seen him without a beard (in Taiwanese culture, beards are usually reserved for men in mourning, so his usual look was not considered appropriate for a celebratory occasion). After our courthouse ceremony in the States, we toasted our parents during an intimate, ceremonial dinner during which we read letters of gratitude to them in place of vows.

So though we hadn't necessarily followed the traditions of a Taiwanese wedding ceremony to a tee, we'd discovered new ways to forge our own path while also honoring our families' wishes. And in the process, we found ourselves teaching each other about our respective upbringings and our traditions, advocating for the ones that felt important to us and learning to let go of those that weren't (the hair combing ceremony, for instance, we were okay to skip). In the four-and-a-half years since then, we've continued to foreground curiosity and openness, unlearning assumptions about what a marriage should be and creating a new, third way of existing that works for both of us in what feels like a true joining of two lives and cultures.

When we were finally able to host our Stateside ceremony in June 2022, more than two-and-a-half years after our luncheon in Taiwan (long story short: pandemic delays), we wanted to similarly incorporate both of our cultures, paying respect to our families' traditions. So when we exchanged rings, we recited the exact vows that my in-laws had said during their own wedding ceremony in August 1977. I wore my mother's pearl necklace, my something borrowed and my something new, an heirloom she would later tell me to keep for good. And throughout our wedding weekend, we served our guests food and drink that gave a nod to our respective backgrounds—salmon for the Pacific Northwest, where my partner grew up; pork belly buns, popcorn chicken, and boba for Taiwan—because what says cultural exchange more than sharing in delicious food?

Weddings, it's said, can often feel like high stakes because they represent the couple's taste, aesthetic and vibe. They're meant to be a way for loved ones to get to know the pair a little better. What I came to recognize, too, is that weddings also offer the couple a window into married life: the art of compromise, how to appreciate differences, and ultimately celebrate your partner for how they show you new ways of being. Having to explain ourselves to each other, it turns out, is a gift, because it means continually learning about the other person and redefining, together, what a marriage can be.